This Time Socialism Is Really Going To Work, Bolivia Edition

/As all good true believers know, the only reason that Socialism has thus far always failed in practice is that real Socialism has never yet been implemented. And thus we have my home town of New York, until now the world capital of capitalism, about to put into office a self-proclaimed Socialist, or maybe Communist, to give Socialism just one more shot.

How could large numbers of seemingly intelligent people believe that this could work? One reason is a remarkable lack of news coverage of the economic status and trajectory of the places that avowedly practice Socialism. My mission here at Manhattan Contrarian is to fix that.

Consider Bolivia. Have you read anything about it lately? They had a presidential election last week, which merited some small interior articles in newspapers I read. The articles I saw before starting to research the topic barely mentioned the current economic situation, and did not mention at all the economic trajectory since the Socialists took power back in 2006.

In the election, which was held on October 20, the nearly 20 year Socialist government has just been voted out by a huge electoral majority. The back story is that the effort to implement Socialism had failed disastrously, as it always does. But just as important is the trajectory followed by the economy under Socialist rule. Here’s the summary: first, an early period of euphoria, where Socialist prescriptions like nationalizations of large businesses (in Bolivia, particularly natural gas sector) funded extensive handouts to government supporters; then a period where the nationalized industries gradually declined until they could not support the handouts any longer; and finally the inevitable economic crisis and collapse.

Way back in June 2015 I had a post titled “On Socialist Death Spirals.” Here is the pithy quote:

{W]hen you look at statistics coming out of fully or largely socialized economies, . . . what you find is that the official statistics for years and decades show growth comparable to, and sometimes faster than, that in capitalist economies; and then one day, it all falls apart.

Here was my analysis of how this works:

Of course the numbers had been fictitious all along. There really was a gradual decline going on, but the numbers didn't show it. And, without knowing all the tricks [used to cook the books in Socialist countries], the main one is obvious, namely counting all or most government spending as a full addition to GDP. Where government owns the main businesses and controls most of the distribution of resources, not to mention prices, the measure of GDP becomes more and more arbitrary.

Now to the case of Bolivia. I had a series of posts about Bolivia in October and November 2019, here, here and here. The occasion was a previous presidential election held on October 20 of that year. Socialist President Evo Morales was finishing his third term and running for a fourth. Unfortunately the Bolivian Constitution limited him to three terms; but as the saying goes about Socialists, “you can vote them in, but you have to shoot them out.” In September 2019, Morales had just gotten his subservient Supreme Court to invalidate the constitutional term limit as contrary to his “human rights.”

In the run-up to that election, on October 1, 2020, The Nation ran the expected big piece touting the spectacular success of the Socialist government, 13 years into its rule. The headline was, “Bolivia’s Remarkable Socialist Success Story.” In my October 3, 2019 post I had some long quotes from that piece, which I will repeat here:

Since taking office in 2006, [President Evo] Morales, a former coca grower and labor activist, has nationalized key industries and used aggressive social spending to reduce extreme poverty by more than half, build a nation with modern infrastructure, and lower Bolivia’s Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, by a stunning 19 percent. For much of Bolivia’s majority-indigenous population in particular, his tenure marks the first time that they’ve lived above poverty and benefited from their country’s tremendous natural resources.

It’s now clear that a redistributionist agenda has not been ruinous to Bolivia’s economy. Far from it: During the Morales era, the economy has grown at twice the rate of the Latin American average, inflation has been stable, the government has amassed substantial savings, and an enterprising and optimistic indigenous middle class has emerged. . . .

Morales also dramatically increased social spending. He poured money into building roads, schools, and hospitals, an expansion of infrastructure that was particularly transformative in the countryside. And he established modest but deeply popular cash transfer programs. . . .

But my post then asked if, even if official government statistics seemed to be showing success, there might be another perspective on what was going on. I found a piece at Bloomberg from February 2019, headline “So Much Gas, So Few Allies Spells Trouble in Populist Nation.” The gist was that Bolivia had long been the only big natural gas producer in its region, which had enabled it to charge premium prices to places like Brazil and Argentina. But those countries were gradually figuring out ways to access cheaper supplies. Oh, and Bolivia’s gas production was also sharply dropping due to lack of investment under the socialist government:

"Basically, there’s a new game in town that has broken the Bolivian monopoly on natural gas in South America," said Fernando Valle, an oil and gas analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. "When you have super high margins somewhere, someone is eventually going to find a way to go into that market and undercut you. That’s what’s happening to the Bolivians now." . . . In 2018, Bolivia’s gas exports fell by about 30 percent, drastically impacting the government’s revenue and the entrance of foreign currency . . . .

The cracks had already begun to appear, even if the cheerleaders at the Nation didn’t choose to see them.

In the October 20, 2019 election, returns on election night appeared to show Morales going down to defeat. But then the vote count was stopped, with no reason given. The next morning, Morales’ people announced that in the final tally their man had won just enough votes to be re-elected without a run-off.

There was an immediate explosion of protests over the election result. Morales called in the OAS to perform a review, and they issued a Report in November. My November 11, 2019 post captured the flavor:

[T]he [OAS] Report makes clear that the efforts of Morales and his people to rig the election were remarkably obvious, crude and amateurish. . . . Really, Evo, you should have been flunked out of Evil Dictator School for having learned so little about how to properly rig an election.

Within weeks, Morales had resigned. Bolivia went through a year of turmoil, leading up to a re-run of the election in October 2020. The victor was Morales’ Socialist side-kick Luis Arce, who has held the presidency since then.

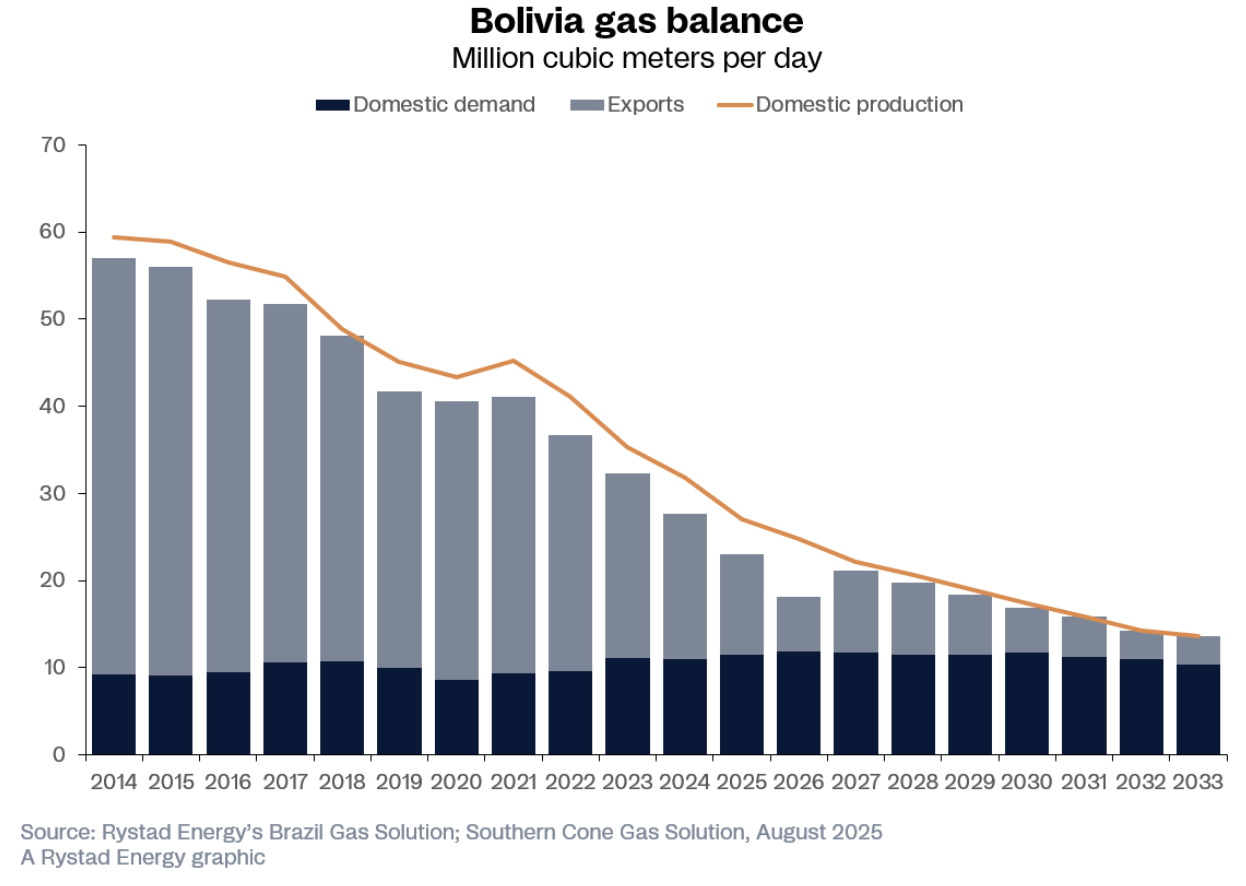

So the Socialists have had another five years to fix the problems and get their program to work. How has that gone? The key industry in Bolivia for funding the Socialist dream has been natural gas production. OilPrice.com had an article on August 28, with data sourced to Rystad Energy. The chart includes data from 2014 to 2025, and projections to 2033:

Bolivia gas production, consumption, and exports

Production has fallen by nearly half since 2014, with declines accelerating in the past few years. I guess that every dollar you reinvest in producing gas is one dollar less that’s available to buy votes.

A more comprehensive picture of the Bolivian economy can be found in an article at the Foundation for Economic Education from August 14. The headline is “Crisis in Bolivia?” Excerpt:

Bolivia’s economy is on the brink of collapse. . . . Facing reelection, [President] Arce refused to cut public spending, reduce subsidies, or liberalize the economy. Instead, the government imposed price controls, stricter currency regulations, and restrictions on importers’ access to dollars. This led to severe shortages of fertilizers, medicines, fuel, cleaning supplies, and food. Prices skyrocketed, and distrust in the boliviano grew. People rushed to exchange bolivianos for US dollars, which were scarce. The central bank imposed further restrictions, pushing demand to the informal market—common in countries like Venezuela or Argentina. Two exchange rates emerged. . . . Given the current trajectory, Bolivia could be headed for a crisis similar to Argentina’s in 2001 or even Venezuela’s. . . .

In short, it’s the same old story. According to the latest data from the IMF, Bolivia’s per capital GDP in 2025 is $4,585. By contrast, the U.S. per capita GDP is given as $89,599.

In the first round of the recent presidential election, held back in August, the MAS party of Morales and Arce got just 3.2% of the vote. That’s what they call “beyond the margin of fraud,” and it looks like they completely gave up on rigging the election. The run-off, held October 20, was between candidates described by NPR here as a “centrist” and a “conservative.” The “centrist,” Rodrigo Paz, won.

NPR says that voters were “outraged by the country's economic crisis and frustrated after 20 years of rule by the Movement Toward Socialism party.” NPR also notes that Paz had “gained traction among working-class and rural voters disillusioned with the unbridled spending” of the Morales/Arce/MAS regime.

Paz takes over in a very difficult situation handed to him by his Socialist predecessors. In the first instance he will have to withdraw the pervasive handouts that the Socialists have put in place. That is not going to be popular. At least Bolivia didn’t have to shoot the Socialists out of office. But they have a very deep hole to dig out of.